"Charisma has nothing to do with energy; it comes from a clarity of WHY, an undying belief in a purpose or cause." —Simon Sinek

When I put

Start with Why on the reading list for

Thriving in the Digital Age, it was because I wanted to encourage the kids in my class to think deeply about leadership. Specifically:

- What exactly do we look for in a leader?

- What type of person inspires us to act—and why?

- What qualities would we, personally, like to develop in ourselves to become stronger leaders?;

- How might we inspire others to follow our lead (for example, if we wanted to convince others to actively support a cause we felt was important)?

In his book,

Start with Why, Simon Sinek argues that "energy excites" and "charisma inspires." To illustrate his point, he compares Microsoft CEOs Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer.

Gates isn't a very energetic speaker, yet he inspires people to follow his lead. Sinek says this is because Gates is optimistic and devoted to what he believes in. Presumably, he has that elusive and hard-to-define quality known as charisma. In contrast, Ballmer can stir up a crowd with his high-energy performances but, according to Sinek, he is not likely to inspire enduring loyalty, because:

"Only charisma can inspire."

While I agree that charismatic people do tend to attract devoted followers or "true believers," something about the exclusivity of Sinek's claim doesn't sit right with me. Was Sinek implying that those of us who lack charisma are incapable of inspiring, destined to become followers? I couldn't accept this conclusion, and I was curious to see how the teens in my class would react. Would they agree with Sinek? If so, how would they describe their own levels of charisma or, more importantly, their chances of becoming inspirational leaders?

What Do We Look for in a Leader?

As we talked about the people whom Sinek describes in his book—Martin Luther King, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Herb Kelleher (founder of Southwest Airlines), and several others—we considered what we felt were important leadership qualities. The students said they valued honesty and being able to communicate effectively, because "No one will follow you if they can't trust you or if they don't know what you're talking about." Talent, passion, vision, integrity, commitment, and empathy were also added to the list.

What Type of Person Inspires Us to Act—and Why?

Responding to the question about who inspires them, the students considered the power of commanding rhetoric (e.g., Obama's speeches), the limited effectiveness of reward systems (especially as sources of inspiration), and the extraordinary impact of impassioned, transformational leaders, such as Malala Yousafszai.

Do We Need to Have Charisma to Be Leaders?

When our discussion turned to the subject of charisma, I asked the group, "If charisma comes from 'an undying belief in a purpose or cause'—as Sinek claims—do we all have the potential to be charismatic?"

The responses I got from the students were insightful, and I'd like to share some of what I learned from them here. One student surprised me by quoting Lawrence of Arabia in his reflection:

"It's always been my view that leaders are not people with a Why, or people with a driving motivation. I mean, of course they have those but so does everyone else. What makes leaders unique is their ability to bring their Why's into reality. In other words, I agree with this quote from T. E. Lawrence (also known as Lawrence of Arabia), 'All men dream: but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dreams with open eyes, to make it possible.'"

This student went on to explain that he interpreted Lawrence's use of the word "dangerous" in a positive way, as meaning "adventurous" or "disruptive to the status quo." He also made another observation worth sharing here:

"Everyone has some greater driving motivation as to why they do what they do, and everyone has something that they are passionate about. We don't need other people to give us a why; we want someone to help us realize our own why."

I imagine all students saying this to their teachers. "We aren't asking you to tell us who we

should be (whether it's interested in Subject X, aiming for College Y, or preparing for Career Z); we are asking you to help us discover who we

already are."

Another student, a young woman who is passionate about music and theater, talked about what it means for a performer to have charisma. She recalled with enthusiasm an article from the

New York Times ("

A Gift from the Musical Gods" by Zachary Woolfe), which asks the question, "How is a performer a leader?" Woolfe writes:

"To experience a charismatic performance is to feel elevated, simultaneously dazed and focused, galvanized and enlarged. It is to surrender to something raw and elemental, to feel happy but also unsatisfied. Charisma calls forth a melancholy, a vaguely unrequited feeling. I’ve caught myself, after certain performances of an aria or a movement, leaning forward, as if drawn against my will. . . . Charisma requires that you acknowledge a new, larger set of possibilities."

So, not unlike leaders in other fields, charismatic performers inspire people to stretch and reach for loftier goals than they would otherwise. Unfortunately, according to Woolfe, "Rigorous training enhances and focuses [charisma], but it cannot create it." So, either you've got it—or you don't.

The young students in my class seemed to agree, saying,"People can know their why, but perhaps not have charisma, or vice versa . . . charisma isn't something that can be taught—one is born with it."

However, one student described Sinek's definition of charisma (as a "clarity of WHY") as "half-true,"noting that:

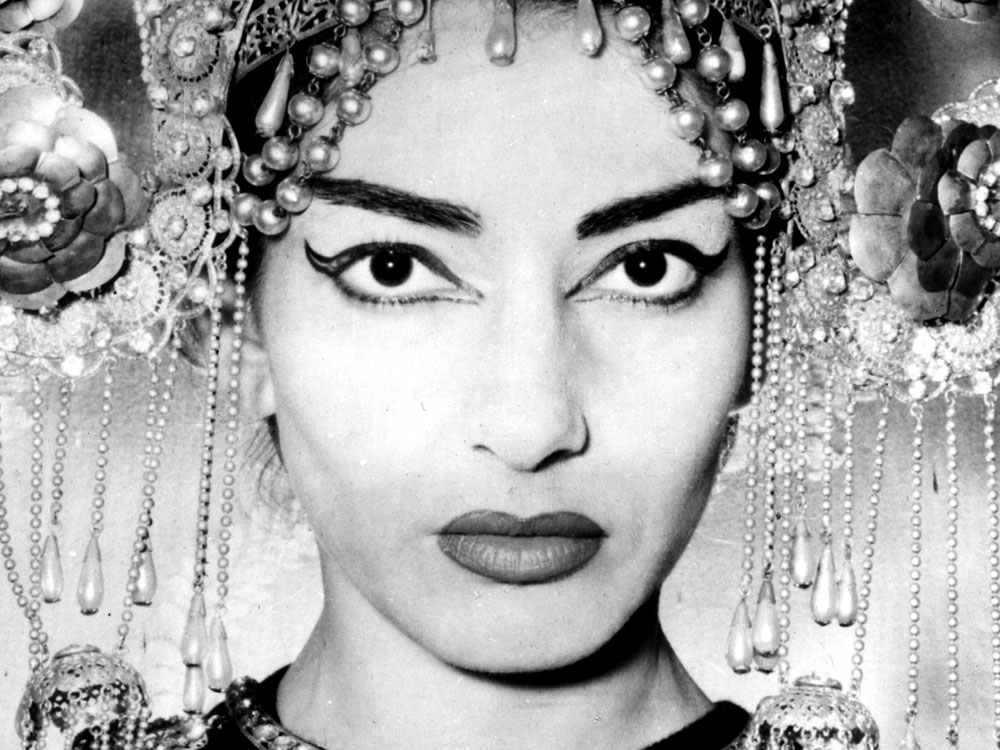

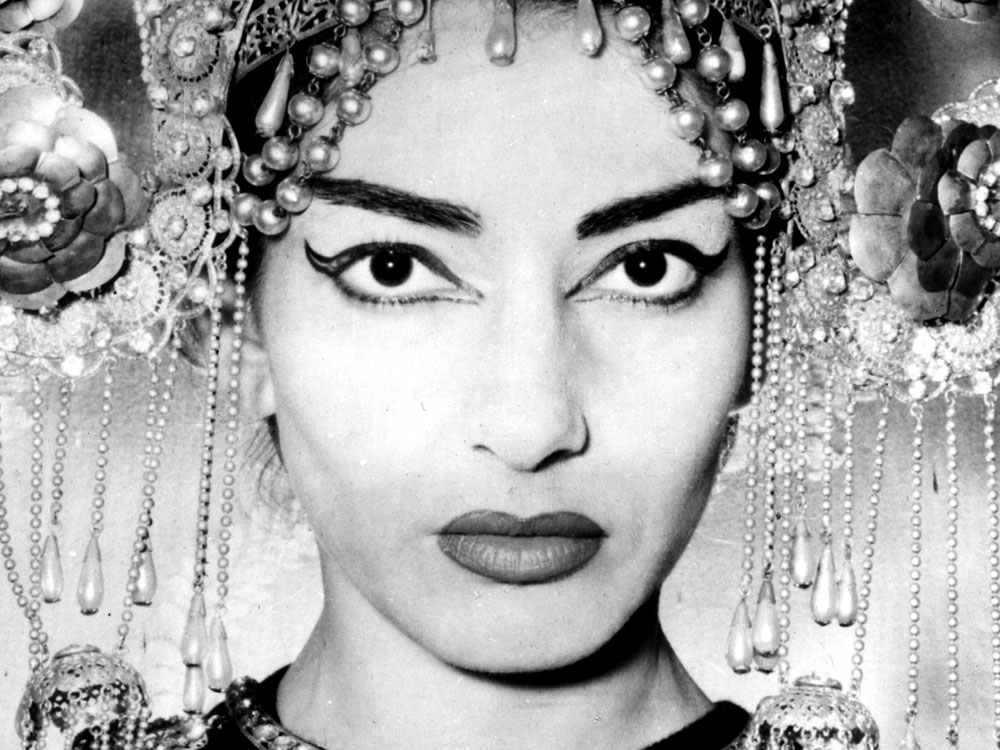

|

| Maria Callas, EMI Classics |

"Charisma is strengthened when the leader or performer knows what their WHY is. For an actor especially: if they haven't asked 'Why?' to each and every line and aspect of the character's notions, it won't be a truthful performance—and even if the performer has the god-given talent of charisma, their performance will lack relevance and the strength to hold the audience's attention. And the same goes for other great leaders. Being able to harness both natural talent and 'the clarity of WHY' together is what leads to a very successful performance."

The same student also argued that an opera singer like Maria Callas is successful not only because she is naturally charismatic but also because she has a clarity of purpose, a genuine passion, that comes across in performances.

So, What Does Charisma Have to Do with Learning?

No matter what we do, whether we are incredibly charismatic or less so, it seems our success—as leaders or followers—is enhanced if we have a clear sense of who we are and what drives us.

This is why I feel it is vital for a student's education to be a process of self-discovery. Returning to Woolfe's article, I'm drawn to the following observation:

"What we generally consider the 'content' of the arts — the notes, the libretto, the bowings, the plot — is actually just the structure that makes possible the crucial thing: watching a performer who is able to connect with fundamental realities. It is not that a singer’s charisma makes a colorful aria sound even better but that the aria provides a platform, a vessel, for us to experience the charisma."

Would it be possible to think of learning in a similar way?

"What we generally consider the 'content' of education — the curricula, the scope and sequence, the technologies, the projects and activities — is actually just the structure that makes possible the crucial thing: helping a learner connect with the fundamental reality of who he or she really is. It is not that a student's aptitudes enable him or her to perform well in class but that the class provides a platform, a vessel, for every student to experience who they truly are."

What do you think?