One of the first revelations had to do with the way they thought about current events. They felt the time they spent on news and education were inseparable, so they reported them as a single activity on the media questionnaire, as if they were one and the same. When I asked them to elaborate, they said they used the internet for research, and their research included keeping up to date on what was happening around the world. It was part of their education. As I questioned them further, I discovered that what they thought of as "news" included not only local politics and major world events but also, in some cases, trending topics on Pinterest or Tumblr. This led me to wonder whether the way in which their generation accesses news online has changed the way they think about the news. (I'm hoping to come back to this topic later in the year, when our class reads Cognitive Surplus by Clay Shirky.)

In response to questions about what mode of communication they preferred, the students stated unanimously—emphatically—that they preferred face-to-face conversation to any other form. If they have a choice and are able to discuss something in person, that's what they would choose to do. When that isn't an option, the more introverted students preferred email to phone; the more extroverted students, just the opposite. Those who preferred email said they liked having time to carefully compose their thoughts and express themselves well. Those who preferred phone said it was the next best thing to talking in person, with less chance of being misunderstood (a problem they associated with email).

All of the students agreed that the risk of being misunderstood increased with email, Facebook, and other social media. One student complained that he was unable to use sarcasm, puns, or humor effectively in an online dialog. He viewed this as especially problematic for him, because he tended to use humor in his everyday (in person) conversations as a way of diffusing tension. Another student observed that she was more likely to have a miscommunication online with someone she either didn't know well or saw rarely.

"With someone you know well and see frequently, there are always plenty of opportunities to clarify, or retract, and thus avoid serious misunderstandings."A few of the students complained that instant messaging and chat were stressful to them because there was too much pressure to type replies quickly, without sufficient time to edit or censor what was being "said."

As we continued to talk about communication in terms of good, better, best, the group acknowledged that alternatives to face-to-face are valuable, even if they aren't ideal. No one was interested in abandoning social media—forms of communication as normal to them as the phone was to their parents—but neither did they want to sacrifice the more personal, real-world connections they continued to value.

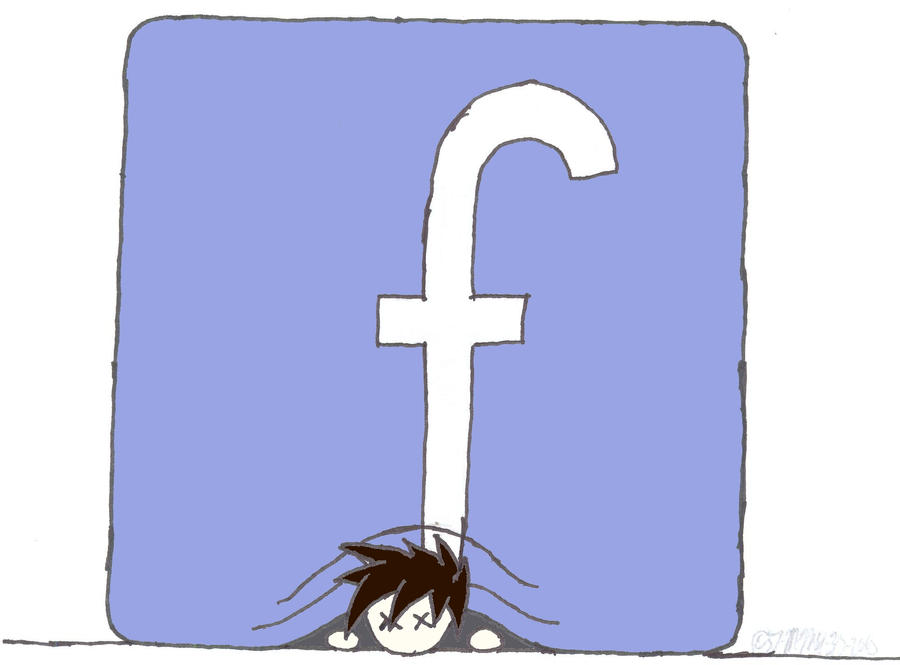

Of all the social media we discussed, Facebook provoked the biggest reaction. Everyone agreed that Facebook did a poor job of representing the "real" person behind the posts. One of the students described how he had gone to look at the Facebook page of someone he had known who had committed suicide, and there was no indication of the young man's depression: his last post on Facebook was a link to a silly video. He felt there might have been a greater chance of seeing a warning sign under different circumstances. Perhaps not—sometimes there are no warning signs before a person decides to commit suicide—but the wide discrepancy between what had happened in the real world and what seemed to be real in the virtual world was troubling to this young man nonetheless.

When I asked the students if they had experienced any strong emotional responses to checking their Facebook pages, I half expected them to say they were mostly unaffected. Although I had heard of "Facebook Depression" (a phenomenon first described by O'Keeffe and Clarke-Pearson in a 2011 report in Pediatrics), my understanding was that it was less likely to impact teens with "high quality friendships" ("Facebook Not Linked to Depression," Huffington Post). So, I assumed it wouldn't be a significant problem for the well-adjusted kids in this close-knit group of friends. I realized I was wrong when the kids got quiet and very serious.

They explained that checking Facebook can lead to depression for several reasons. One, "when you see what other people are doing, you automatically compare their lives to your own life, which may seem relatively inadequate." They emphasized that this was true "even when you know people on Facebook are going out of their way to appear better, happier, and more exciting than they are in 'real' life." Two, mistakes don't go away: when you post something on someone else's Facebook page and then decide you don't like what you've posted, you're unable to remove it; so, you are forced to see your "mistake" over and over and over again.

"Unlike a spoken comment said in passing that you wish you could take back, the written comment doesn't vanish in the air. It sticks around."How true.

It was sobering for me to talk honestly with a group of teens I respect about their perspectives on social media. I don't know if their experiences are representative of teens in general or not, but I felt it was worth sharing what I learned from them.

No comments:

Post a Comment